Diplomatic Transcription

“I like Englishmen,” once said a Russian woman to Sir Robert Morier, the late English Ambassador at St. Petersburg. “Every Englishman is an island.”

Sir Robert, far from being offended, seemed rather pleased with the remark, and even repeated it to others as a compliment to his country. He rather gloried in the pronounced individuality of the country he represented, and no doubt there is something very fascinating in the excessive insularity of the English mind.

But in this, as in other matters, there is a “revers de la médaille.”

If I am allowed to illustrate this in my own case, I may point to the comments on my article in the Fortnightly Review for this month (“Russia and the Rediscovery of Europe”). I am merely a frank exponent of Continental views, which English insularitу finds it so difficult to understand.

All that has been said in that connection only confirms the truth of my observation and justifies the Continental criticism, which, in very mild and modified form, I ventured to press upon my English readers’ attention.

Instead of altering my views, the comments upon my article more than ever convince me how difficult it is for Englishmen to become good Europeans. At present I gladly admit the English Government are doing their utmost to remove this reproach.

The last speech of Mr. Curzon, for instance, was really first-rate in the soundness of its views—in the logical development of its conclusions.

“The Concert of Europe,” said he, “is the Cabinet of the Continent—the Privy Council of the nations. It was the greatest advance in international law and in international ethics that this century has seen.” But how is it that whilst the Government are doing their best, explaining elementary truisms and pointing out most obvious facts, a vociferary portion of the public Press, with such peculiar perversity, arrays itself against Europe and against the Ministers of the Queen?

Is it not a reasonable presumption that when the six Powers—divided as they are by so many rivalries, and who each approach the subject from a standpoint entirely different from that of any of the other five—should all come to the self-same conclusion there must be some very solid ground for such unanimity?

Remember how closely we in Russia, for instance, are united to the Greeks by ties of religion and tradition, and how the personality and position of Queen Olga and her family awaken in us the liveliest feelings of respect and sympathy. The German Emperor is also closely united to the Greek Royal family. Then, again, King George is the brother of the Princess of Wales and of our Dowager-Empress.

Yet all these personal considerations could not blind either Russia or Germany to the obvious duty which lay before them as the custodians of the peace of Europe. And France, Austria, Italy, and England are all agreed upon this as the paramount necessity.

The Powers seem at last perfectly unanimous in believing that the integrity of the Ottoman Empire must, on the whole, be maintained, though in Crete—where the promised reforms have never been applied—the independent sovereignty of the Sultan must be abolished at once.

The attempt of the Greeks, however, to begin a general scramble must be absolutely checked. Yet many voices in England insist upon the opposite view.

Whenever England separates herself from the others, Europe immediately suspects her of some concealed perfidious desire to seize something for herself, a la Cyprus.

And no wonder. I call to mind some lines of my old friend Russell Lowell—

He has seized the idea, by his martyrdom fired,

That all men, not orthodox, may be inspired.

And it really seems as if in your insular mania for independence and individuality, you now support the Greek cause simply from the ingrained impulse to oppose whatever policy commends itself to the mature judgment of the Continent. What comes next? Are you going to dissent from the arithmetical rule of three? That would be almost as foolish as to protest against the rule of six—in the Eastern Question. Since when did England feel so burning a devotion to the beaux yeux of the Hellenes?

Byron, no doubt, fought and died for them, and that death is as precious to Russian as to Greek memories. He was an English volunteer at Missolonghi, like our own volunteers in the Balkans, but to Byron’s contemporaries even Navarino was an “untoward event,” and the English, as a nation, only reluctantly assented to Greek independence.

This reluctance was based on jealousy of Russia. Greek soil was chosen for a display of prejudice against Russia. If at this moment—to imagine what is quite out of the question—Russia, forgetting her duty to Europe, were to aid and abet the Greek insurgents in Crete, and the Greek armies in Epirus, what a change would come over the spirit of your dreams! The Greeks would be once more regarded as “pestilent bandits” who do not pay their debts, and whose political enormities would once more warrant the occupation of Athens by English troops.

But as at present Russia is loyal to Europe, a noisy fraction of England insists upon their country being disloyal to the Concert, using all their eloquence to inflame Greek passions and incite that country to a breach of the peace.

A German lady, enthusiastic on European politics, but not very well acquainted with the English language, and with no intention at all of being sarcastic, translates the “six Powers (Machte) as the Six Mites.”

And really, if the six Powers had submitted to the will of the reckless insurgents or the impatient patriots, they certainly would have played the part of political “mites.”

OLGA NOVIKOFF (O.K.).

Essay Subjects

People Mentioned in the Essay

- Baron George Gordon Byron

- Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany

- Empress Maria Fyodorovna Romanova of Russia

- George Nathaniel Curzon 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

- James Russell Lowell

- King George I of Greece

- Queen Consort Alexandra of Denmark

- Queen Olga Konstantinovna Romanova of Greece

- Queen Victoria of Great Britain

- Sir Robert Morier

Cities Mentioned in the Essay

Editorial Notes

Contains a reference to Novikoff, Olga. “Russia and the Re-Discovery of Europe.” Fortnightly Review 61, no. 374 (April 1897): 479–91.

A reader response to Novikoff’s essay appeared in The Observer (London), April 18, 1897:

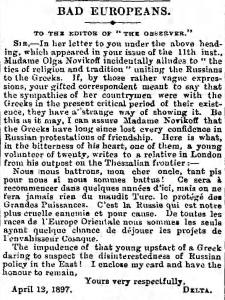

“To the Editor of ‘The Observer.”

Sir,—In her letter to you under the above heading, which appeared in your issue of the 11th inst., Madame Olga Novikoff incidentally alludes to “the ties of religion and tradition” uniting the Russians to the Greeks. If, by those rather vague expressions. your gifted correspondent meant to ay that the sympathies of her countrymen were with the Greeks in the present critical period of their existence, they have a strange way of showing it. Be this as it may, I can assure Madame Novikoff that the Greeks have long since lost every confidence in Russian protestations of friendship. Here is what in the bitterness of his heart, one of them, a young volunteer of twenty, writes to a relative in London from his outpost on the Thessalian frontier:—

Nouns nous battons, moucher oncle, tant pis pour nouns si nouns sommes battus! Ce sera à recommencer dans quelques nunées d’ici, mais on ne fera jamais rien du maudit Turc. le protégé des Grandes Puissances. C’est la Russie qui cet notre plus cruelle ennemie et pour cause. De tontes les races de l’Europe Orientale nous sommes le s seuls ayant quelque chance de déjouer les projets de l’envahisseur Cosaque.

The impudence of that young upstart of a Greek daring to suspect the disinterestedness of Russian policy in the East! I enclose my card and have the honor to remain,

Yours very respectfully,

Delta.

April 12, 1897

Citation

Novikoff, Olga. “Bad Europeans.” The Observer (London), April 11, 1897.

Response

Yes

Facsimile Image